Introduction

The unique and extraordinary microorganism that produces the avermectins (from which ivermectin is derived) was discovered by Ōmura in 1973 (Figure 1). It was sent to Merck laboratories to be run through a specialized screen for anthelmintics in 1974 and the avermectins were found and named in 1975. The safer and more effective derivative, ivermectin, was subsequently commercialized, entering the veterinary, agricultural and aquaculture markets in 1981. The drug’s potential in human health was confirmed a few years later and it was registered in 1987 and immediately provided free of charge (branded as Mectizan)—‘as much as needed for as long as needed’—with the goal of helping to control Onchocerciasis (also known as River Blindness) among poverty-stricken populations throughout the tropics. Uses of donated ivermectin to tackle other so-called ‘neglected tropical diseases’ soon followed, while commercially available products were introduced for the treatment of other human diseases

Many excellent, eloquent and comprehensive reviews covering the discovery, advent, development, manufacture and distribution of ivermectin have been published by those intimately involved with the various stages.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 It would be folly to replicate those here. Instead, it is the current status, beneficial global health impact and exciting future potential that ivermectin has to offer to human health worldwide that will be the focus of attention.

Today, ivermectin remains a relatively unknown drug, although few, if any, other drugs can rival ivermectin for its beneficial impact on human health and welfare. Ivermectin is a broad-spectrum anti-parasitic agent, primarily deployed to combat parasitic worms in veterinary and human medicine. This unprecedented compound has mainly been used in humans as an oral medication for treating filarial diseases but is also effective against other worm-related infections and diseases, plus several parasite-induced epidermal parasitic skin diseases, as well as insect infestations. It is approved for human use in several countries, ostensibly to treat Onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis (also known as Elephantiasis), strongyloidiasis and/or scabies and, very recently, to combat head lice. However, health workers are increasingly utilizing it in an unsanctioned manner to treat a diverse range of other diseases, as shown in Appendix 1.

The past: unmatched successes

Perhaps more than any other drug, ivermectin is a drug for the world’s poor. For most of this century, some 250 million people have been taking it annually to combat two of the world’s most devastating, disfiguring, debilitating and stigma-inducing diseases, Onchocerciasis and Lymphatic filariasis. Most of the recipients live in remote, rural, desperately under-resourced communities in developing countries and have virtually no access to even the most rudimentary of medical interventions. Moreover, all the treatments have been made available free of charge thanks to the unprecedented drug donation program.

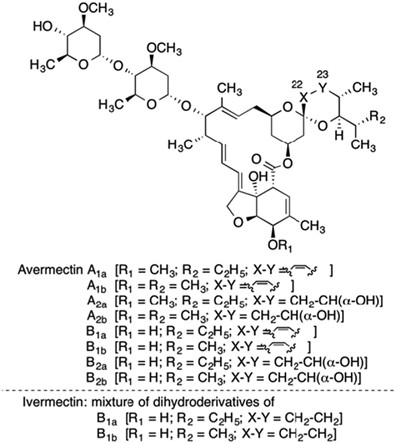

When the avermectins were discovered, they represented a completely new class of compounds, ‘endectocides’, so designated because they killed a diverse range of disease-causing organisms—as well as pathogen vectors—inside as well as outside the body. The first publications on avermectin appeared in 1979, describing it as a complex mixture of 16-membered macrocyclic lactones produced by fermentation of the actinomycete Streptomyces avermitilis—later re-classified as S. avermectinius (Figure 2). The avermectin family displayed extraordinarily potent anthelmintic properties.15, 16, 17 Ivermectin is a safer, more potent semisynthetic mixture of two chemically modified avermectins, comprising 80% of 22,23-dihydroavermectin-B1a and 20% 22,23-dihydroavermectin-B1b (Figure 3).

Ivermectin was a revelation. It had a broad spectrum of activity, was highly efficacious, acting robustly at low doses against a wide variety of nematode, insect and acarine parasites. It proved to be extremely effective against most common intestinal worms (except tapeworms), could be administered orally, topically or parentally and showed no signs of cross-resistance with other commonly used anti-parasitic compounds. Marketed in 1981, it quickly became used worldwide to combat filarial and other infections and infestations in livestock and pets.

Registered for human use in 1987, ivermectin was immediately donated as Mectizan tablets to be used solely to control Onchocerciasis, a skin disfiguring and blinding disease caused by infection with the filarial worm Onchocerca volvulus, which afflicted millions of poor families throughout the tropics. Some 20–40 million people were infected prior to the launch of large-scale control interventions, with around 200 million more at risk of infection.18, 19, 20 Human infection has been tackled in endemic areas through annual or semi-annual mass drug administration of ivermectin and only 21–22 million people (almost exclusively in Africa) remain infected with O. volvulus.21

Since the prodigious drug donation operation began, 1.5 billion treatments have been approved. Latest figures show that an estimated 186.6 million people worldwide are still in need of treatment, with over 112.7 million people being treated yearly, predominantly in Africa.22 Actual treatments declined in 2014/2015 due to the planned closure of the highly successful and innovative African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control and a subsequent delay before the more comprehensive replacement, the Expanded Special Project for the Elimination of Neglected Tropical Diseases in Africa, became established and operational, plus deferment of some treatments until 2016.

The African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control was created in 1995 to establish community-directed treatment with ivermectin to control Onchocerciasis as a public health problem in African nations that represented 80% of the global disease burden. For long the sole agent used in control efforts, ivermectin has been so successful that the goal has now switched from disease control to worldwide disease elimination. For most afflicted countries, nationwide Onchocerciasis elimination is within reach and there is hope that the global elimination target of 2025 will be achieved.23 Latest models indicate that if the 2025 target (or sooner) is to be achieved, 1.15 billion more treatments will be required,24 assuming that the absence of drug resistance continues.

In the mid-1990s, ivermectin was found to be an excellent treatment for Lymphatic filariasis, leading to the donation program being extended to cover this disease in areas where it co-exists with Onchocerciasis (Figure 4). In 2015, almost 374 million people required ivermectin for Lymphatic filariasis, with 176.5 million being treated.25 In 2015, 120.7 million ivermectin treatments were approved for Lymphatic filariasis, an accumulated 1.2 billion treatments being authorized since the drug donation program was extended to cover the second disease in 1998.26

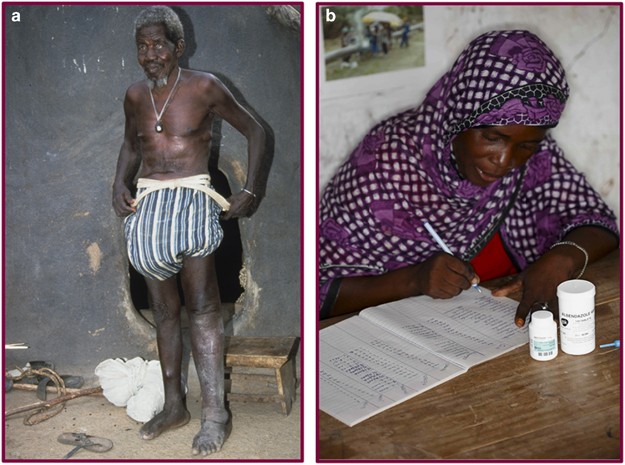

(a) An African man with blindness, skin damage and disfigurement due to Onchocerciasis and Lymphatic filariasis. (b) A community-directed distributor of ivermectin recording the administration of a combination of ivermectin with albendazole, used to treat and protect individuals in areas where the two diseases co-exist—both diseases being poised for elimination as public health problems within a decade. (Photo credits: Andy Crump).